The relationship between "joker" and "jokee" is fraught with tension. For a joke to be "funny," the cultural synchronization between the two parties has to be at a level where media, historical, and literary references are mutually understood, moral senses are somewhat aligned, and everyday minutiae share some sort of common ground. When these backgrounds stray too far from each other, the missed connection between joker and jokee can result in a failure to receive the wink and the nod of trust and understanding. Because jokes demand differing levels of these understandings between each party (for punchline to use the element of surprise), a joke can be a matter of high stakes. One wrong move and a joker could hurt some feelings or, worse, not get a laugh.

In an interactive audience, that occasion might be marked by a stone-faced uttering of the phrase I Don't Get It; a passive audience (TV/studio audience) might just stay silent. This is all familiar. The goal of jokecraft in this depiction relies on a construction of trust between joker and jokee, but it seems to be well understood now that with each effort of larger media entities to reinforce and institutionalize "mainstream comedy",[1] a correlating effort to destroy that relationship emerges with a similar force elsewhere on the comedy spectrum. Andy Kaufman reading the entirety of The Great Gatsby to an audience expecting stand-up is certainly a point of reference here, but there seems to be a relevant gesture of hostility between comic and audience that somehow side steps the outwardness of this sort of "anti-humor" by occupying the space of the "Indecipherable Punchline."

The Indecipherable Punchline is a joke resolution that purposely fails to convey information central to the understanding of the exchange. Unlike the bombed joke, this joke space relies on a strategic manipulation of audience, usually by luring one group/demographic in for an established brand of humor, but enters into a purgatory zone of signs and contexts rather than a space of semi-surprising, successfully transmitted information. A slapstick comedy of relationships rather than of bodies or materials.

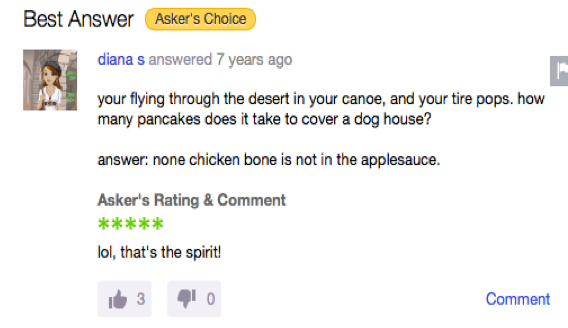

It's important to note early on that it is not the nonsense punchline of "Surrealist Humor": an example found from an exchange between users lazytramp789 and diana s on Yahoo! Answers shows an example of what that separate joke archetype might look like:

The joke here: the receiver thought that the joker was going to have a cleverly logical solution that completed the already surreal set up, but, in fact, did not.[2] Like all punchlines that rely on onomatopoeias, gobbledygook, funny noises, and nonsense, the medium is the message. These violations of causal reasoning often stem from various 20th century avant garde movements, Dada, Surrealism, etc., but their induction into the mainstream sense of humor has left them somewhat cold and lifeless.

The Indecipherable Punchline relies on a style of humor separate from the traditional methods of comedy because, though it relies on illusionistic (yes, "mainstream") humor methods as a platform, the humor lies somewhere between the very gesture of a person telling the joke and of the reaction of (not) receiving the joke. The experience of not only missing the joke, but also of completely failing to recognize what is presented as a logical, funny punchline points towards a humor of action that is present in the moment (as opposed to pointing the jokee to imagine some depicted moment of humor).

A true pioneer in this comedy is the '90s sitcom "Frasier." The Seattle-based Cheers-spinoff is made up of social and workplace mishaps of two psychiatrists, their father, and his home healthcare worker. "Frasier" maintains a semi-hostile method of twisting distinct target audiences against each other throughout its run, and each episode seems to offer an iconic example of indecipherability. Primarily, this is done is by aligning characters with "high" and "low" (class, sophistication, education, humor) while writing jokes along the same fault lines. The result is a series of puns and jokes that accommodate a mass, cable TV audience while using semi-obscure, elitist references as core material. As a show structure, it is especially notable that this combination of tactics simultaneously appears to function as a first step towards depicting Whiteness as an entity, rather than as an unseen fog. In some ways, it uses the standard formats of comedy so easily recognizable as mainstream (i.e. 30 minute time slot situational comedy about a white, Christian family), in others, it places the traits of these people at the butt of each joke. Frasier's and Niles' qualities as pearl-clutching liberals and their father Martin's qualities as an working-class, conservative, retired cop, especially become central points for comedy.

One joke that demonstrates the high/low clash is in S1E19, when a punchline (indicated by laugh track) occurs while Frasier and Niles explore a chair showroom, "Ideally, we're looking for something with the presence of a Mies van der Rohe and the playful insouciance of an early Le Corbusier." The roaring laugh track indicates that the comedy lies in the fact that the two are in the wrong setting for this language. Without an audience's point of reference for the work of the two mid-century designers, however, the phonic textures in each name, the purposely exaggerated vocabulary, and the lack of follow up allow for the joke to become more of a place holder for the assertion that "a joke was made" rather than it functioning as a vehicle for pun, wit, or some other comic device.

Equally relevant (for different reasons) is found in S1E20 when Frasier says, "I guess that's because I'm Jung at heart!" I remember the sense of absurdity without the point of reference at one point: "I guess I'm young at heart!" confirmed as a joke by a strong laugh track. [3]

There is a direct contrast with these jokes to the less-considered (not especially choreographed) slapstick segments and other base comedy moments throughout the show. A completely obscure reference gets bludgeoned by use of sophomoric humor or catch phrase jokes (Bulldog's frequent repetition of "This stinks! This is total B.S.!" as a reliance on a sitcom mainstay). There is a twisting of target audiences between the Roz/Martin (low) alliance to the Niles/Frasier (high) alliance to systematically use the failure of the audience as a joke within itself (a function that is enabled by a context of channel number, time slot, surrounding jokes, social expectations for sitcoms, etc.) That joke of audience failure remains distinct and separate from the depicted comedy of Frasier.

By becoming action-based rather than language-based (i.e. with comedy in the action of telling the joke rather than in the content of the joke), this form begins to fall into the realm of the previously mentioned concrete comedy that David Robbins outlines. In this comedy space, one finds connections with other hostile relationships between producer/consumer outside of a comedy context, especially in pieces such as Piero Manzoni's Merde d'Artista (Artist's Shit, 1961), a joke that could be deciphered as a bitter gesture regarding the art market, a pun of "artist as producer," and simultaneously function as a commodity within that same art market.

If the history of comedy finds its significance in the freedom of the jester to speak truth in the face of monolithic power, perhaps that hostility becomes the only way to push back against institutionalized, softened comedy and commentary. An impulse for that hostility may reveal as much about where power lies, as well. Whether or not Frasier or its implementation of the indecipherable punchline actually becomes political is unclear (while the high/low cultural split inhibits the normalization of almost any characters' way of life, it remains fairly aloof), but developing language around this tool is necessary for being able to properly recognize its use in the future.

-------------------

1 A term extensively meditated on by artist David Robbins in efforts to theorize the history of Concrete Comedy ("the comedy of doing rather than saying"). He distinguishes Mainstream Comedy as humor that relies on verbal structure, illusionism (reference outside of the now), and narrative.

2 The irony of the English speaking comic-landscape is that the first joke introduced to infants, as they develop understanding of a more leisured use of language, might be, "Why did the chicken cross the road?" ("To get to the other side.") The joke is, of course, "you were expecting this to be a joke." But how could they have been? They don’t even know what that is.

3 Though recognizable as a standard psychiatric pun, perhaps the real joke is that Frasier has always been a die-hard Freudian and would never admit to this.